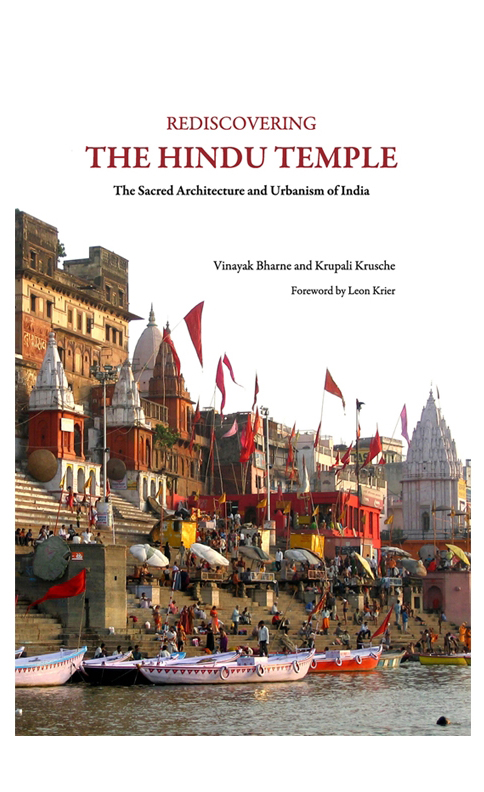

Following his 24-chapter edited volume, The Emerging Asian City: Concomitant Urbanities and Urbanisms, Los Angeles based urbanist Vinayak Bharne’s co-authored book Rediscovering the Hindu Temple: The Sacred Architecture and Urbanism of India opens a refreshing and provocative dialogue on the presence and role of Hindu temples in contemporary India. Praised by the noted architect Leon Krier as “not only relevant for the sub-continent but contribut(ing) importantly to the general re-evaluation of traditional values globally,” this is one of the few books that goes beyond stylistic examinations into the urban and socio-cultural aspects of Hindu temples. We spoke to Bharne about the key findings of this study, and the larger agenda behind this effort.

1. You have been writing on the urbanism of Hindu temples for more than a decade now. How did you develop and interest in this topic?

It is not exclusively an interest in Hindu temples as much as the role of religion as a catalyst and agent for urban transformation. In places like India, top-down urban reform through regulation and formal means will only go so far – Indian cities are way too ambiguous and complex. There are many other forces that are insinuating effective urban change, and should be recognized as such. Religion is one of them. When I use the term “religion” here, I do not refer to a set of beliefs, rather a dominant cultural phenomenon that continues to bear an indelible influence on the Indian city.

Since I was born and raised in a Hindu family in Goa, the places and workings of Hinduism have been well known to me, so it obviously became my conduit to explore this larger topic.

2. What are some of the “rediscoveries” that emerge through your recent book?

Most worthy books on Hindu temples, written by historians and anthropologists, have tended to focus rather dominantly on their historiographical and stylistic dimensions as classical objects. But what about the millions of modest populist temples and wayside shrines that dot Indian cities and villages? Many of today’s biggest temples have in fact evolved from such wayside shrines through process quite different from conventional development. As such, these shrines, innocuous as they seem, are not simply nodes of solace for the millions of underserved who simply want a stake in the city, but also potent lynch-pins for social, economic and physical change.

Wayside shrine in Banaras (photo by Vinayak Bharne)

Street outside Arunachaleshwara Temple, Tiruvannamalai (photo by Douglas Duany)

Hanuman Mandir, Connought Place, New Delhi (photo by Hanna K. Tandon)

Further, temples are not just embellished buildings, but parts of larger place types and habitats where ritual and commerce overlap, making them corporations and in some cases entire towns devoted to sacred activity. There are distinct typologies of sacred Hindu habitats– from modest hamlets like Madkai, to sizable towns like Srirangam or Chidambaram, to complex cities like Ujjain and Banaras. I have been documenting them for over a decade now, and trying to come to terms with what exactly they mean. They are different from typical Indian cities, because many of the daily forces that sustain them are different in the first place. We need specific attitudes and approaches towards envisioning their future, and engaging with them.

Comparative study of Hindu temple towns in India (copyright Vinayak Bharne)

This also provokes a rethinking of heritage conservation. Typically, we tend to preserve temples as buildings, but forget their inextricable links to surrounding habitats and ecologies. In many cases these surrounds are part and parcel of the ritualized sacred landscape. What then are the means to really conserving the heritage of these places, holistically, while letting them embrace change?

Documentation of annual Navadurga Temple festival in Madkai, Goa by Bharne (copyright Vinayak Bharne)

The book also traces the place of temples within the Indian metropolis. There are two parallel phenomena here – you have franchised built-from-scratch temples like the Akshardham that are enormous physical and economic investments, versus temples that evolve from more stealthy (and illegal) means. The important thing is that they will both persist and influence millions of lives. How then do we embrace their specific planning potentials?

So this is the larger rediscovery this book puts forth – the idea of a temple beyond just an embellished object; the idea of a temple as a complex cultural entity: a historic artifact, an evolving habitus, an urban agent, and contemporary place, all in one. One of the larger agendas behind this study is thus to call for a broader nexus of religion and urbanism into mainstream Indian planning regimes that conveniently ignore this phenomenon.

As a practicing urbanist, how do you want to engage yourself with these temple towns in real life?

That is exactly what I am trying to figure out! It is easy to create master plans for these places, and then pack your bags and leave. It is far more difficult to trace the real trajectories that are going to chart the future of these places. Don’t get me wrong – we need strategic master plans, guidelines, etc., but in India, we all know that there is no guarantee of their efficacy. We therefore need parallel strategies to create real positive legacies, and that can only come by engaging with both populist and administrative structures simultaneously. So last year, we did an experimental studio in Banaras to test the potential of this idea…..and it was very interesting.

Do elaborate….

Banaras is one of India’s oldest and most prominent sacred Hindu cities, but beneath the sacredscape, there is also a growing city gripped with increasing population, housing shortage, traffic congestion, poverty, social oppression etc. The current planning instruments of the city are pitifully one dimensional – centered only on land-use, zoning, conventional master planning, municipal bureaucracy etc. – even as a whole bunch of alternative engines such as non-profits and social workers are bringing all kinds of positive change.

Rethinking Banaras (photos by Vinayak Bharne)

Our team comprised sixteen (non-Indian) graduate students from the USC Price School of Public Policy with multiple backgrounds – urban planning, public health, policy, political science, architecture, psychology etc. – and this was great because they each re-read the city from their own perspectives, without any preconceptions, and with a lot of naivety. We collaborated with faculty from Banaras Hindu University for their local expertise. The students were unleashed into various portions of the city, depending on their topical interests, and together we interacted with the entire transect of the urban populace – from hermits on the Ghats and rikshawalls, to university professors and the municipal commissioner.

What resulted was a multi-faceted muddle of interventions and actions – top-down and bottom-up; physical and non-physical; sacred and mundane – with ambiguous lines separating them. Because it was an academic exercise, we could on the one hand contemplate provocative large-scale strategies like a new city on the eastern bank of the Ganga River to mitigate congestion, Floor Area Ratio Transfer strategies from the Ghats to the city outskirts to amalgamate preservation and economic development, and ambitious infrastructural ideas to divert the annual Ganga flood waters. On the other, there were modest decentralized ideas like revitalizing pilgrimage halting spots through local participation or planting amenity hubs throughout the city. There were sensitive socio-sacred strategies like bringing back Ayurveda into the city’s public health policies. Or dealing with social exploitation and prostitution by tapping into the non-profits already at work. Or creating autonomous trusts to give select temples jurisdiction over their physical surroundings that are currently under the purview of a singular municipality and therefore neglected or ill-maintained. This kind of multidisciplinary approach is quite different from the ongoing planning efforts that are currently in the pipeline- this muddle is what planning is really all about!

So what is next in your pipeline?

I am hoping to return to Banaras again in 2014, complete the study in some cogent form and give it to the city for at least their curiosity if nothing else. I have also spoken to my colleagues at Benaras Hindu University about creating a web forum titled The Banaras Initiative, where existing and onoing scholarship and vision that already exists on/for Banaras (there is a lot of it) can actually be consolidated and presented more systematically to a bigger audience. Would love to do a similar studio or real effort in Srirangam, or Puri. But for now, my book on Japanese architecture and urbanism is set for release in March 2014. And I have a grant to do an incremental enhancement plan for the surroundings of one of Japan’s most revered Shinto shrines, the Ise Jingu.