The term “density” has developed a tarnished reputation in our time. It has become synonymous with mid and high rise buildings, typically designed as homogeneous, repetitive, self-referential projects that rarely respond to their adjacencies, surrounding streets or their location within the city. The uncritical obtrusion into single-family neighborhood fabric, or the haphazard mushrooming of slabs and towers, represents not only the denial of a coherent urban form and public realm, but the reduction of the very idea of city-making into an unchecked, rapacious capitalism.

There are two planning tools that have perpetrated this attitude – Floor Space index and Coverage. Floor Space Index (FSI or FAR) establishes the optimum building envelope within a lot per its specific zoning designation. It is expressed as a number: A FSI of 3 means that the total buildable area can be up to thrice the lot area. Coverage in turn establishes the extent of the building footprint on a lot, or the amount of open space to be accommodated within the lot. It is expressed as a percentage of the lot area: A Coverage of 75% means that at least 25% of the total lot area must be open to sky space. While both FSI and Coverage help quantify building to land ratios, they do not offer any means of appropriating building form to its surrounding context. Further, FSI offers assembled lots a considerable buildable area over individual lots, incentivizing larger buildings which have a negative effect within finely grained communities. In short, FSI based codes are poor predictors of urban form. They reduce development to a one-shoe-fits-all approach, with developers packing as many units as possible within a maximum allowable envelope, regardless of context.

The idea of “Blending Density” represents a critical counterpoint to this syndrome. It advocates for a heterogeneous distribution of buildings on a lot or block basis. It replaces the homogeneity of FSI-based development with a calculated massing diversity that responds to and evolves from the desired character of its physical context. For instance, the FSI target of a single tower floating within a lot can also be achieved through a combination of a tower and mid-rises within the same lot appropriately massed to respond to their surrounding streets. Likewise, an FSI of a single mid-rise can be recalibrated as a combination of mid-rise and low-rise buildings making the development compatible with adjacent single-family houses. Thus, a final FSI target need not be the result of a single literal extrusion, but the average of various FSI components within a site, each carefully conceived in response to context.

How does one recast the FSI based regulatory framework to accomplish this? First, the FAR number can be replaced with minimum and maximum building heights that are carefully regulated on a block by block basis to respond to the streets and neighboring buildings. Larger avenues and parkways can be coded to take bigger and taller buildings, smaller neighborhood streets can repeat the scale of dwellings.

Second the set back requirement can be expanded to articulate building frontage, that is, the desired scale and character of the block or lot face. Blank street walls can be disallowed. In certain areas, ground floors can be required to be taller to accommodate retail and commercial uses over time. Where appropriate, ground floor units can be required to have direct access from the streets through a number of contextually appropriate transitional elements such as porches, stoops, dooryards to lobbies. Compound walls where customary can be regulated to ensure formal harmony. The interface between the public and private realm can thus be consciously calibrated block by block, street by street.

Third, regulations can spell out the allowed parking disposition within a lot to ensure that it is concealed from the public realm. For instance above-grade parking may not be allowed within the first 25% of a lot. Parking podiums can be mandatorily lined towards the street, and the number of parking entries per block face can be accordingly specified. In contrast to conventional zoning, a minimal set of mandatory Urban Standards on building placement, building profile, frontage, and parking location can thus ensure a predictable and positive relationship between the building to the public realm, with the architecture and specifics remain open-ended.

While recasting FSI codes through height and frontage standards does help regulate the public –private interface, it does not necessarily guarantee a parallel performance standard within the lot interior. A perfectly compatible project as seen from the street may be a terrible building within – a “motel” for instance, with a central courtyard given to parking and surrounded by multi-level corridors as the only means of circulation to the units. As such, all units get minimal privacy and direct light and air from only one side.

FSI-based zoning can therefore be advanced through performance standards for the lot interior. Non-mandatory guidelines can articulate how an open space within the lot interior should be adequately landscaped, how public rooms rather than blank walls should face a communal courtyard, or how the various units should have adequate private space. While these may not be mandatory, they can be used as a checklist by developers to both understand the larger intentions of the code and thereby ease the entitlement process.

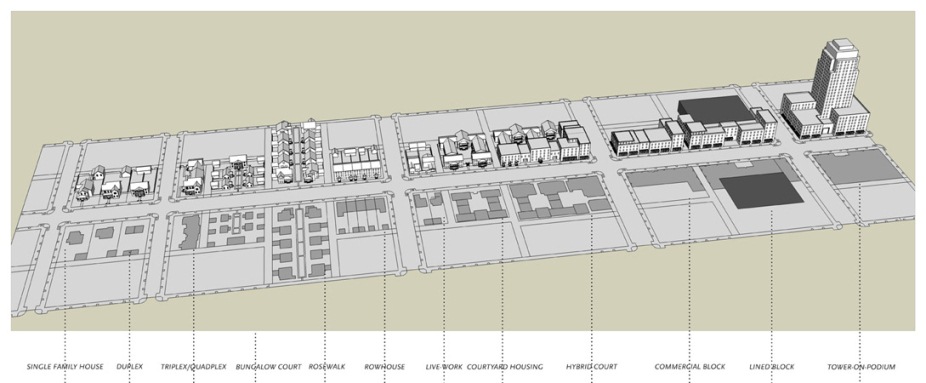

FSI-based zoning can also be further advanced through the introduction of typological regulations. The term typology is essentially a classification of buildings not by use, but per their objective spatial and formal dimensions: access, open space, circulation, spatial organization and parking. For instance, an entire menu of residential types can be organized by intensity from the least dense (Single-family house, Duplex etc) to the most dense (Slabs,Towers etc), creating a DNA for residential development, each with their respective density (units/hectare) or FSI numbers. Hardly a one-shoe-fits-all menu, this typological calibration needs to be essentially place-based emerging from the history, climate, and market realities of that particular city or country.

The code can then specify which of these types are appropriate in which zone. For example, the tower might be allowed in the urban core, or along major corridors, but not within single-family neighborhoods. A duplex may be allowed within a neighborhood, but not along a major commercial corridor. Developers and architects can then choose and locate the allowed building types along specific streets without worrying about compatibility concerns. The typological menu, coupled with the Urban Standards can thus provide an alternative planning tool prioritizing responsible urban form of land-use.

The challenge of course is how one gets from here to there. Changing conventional zoning is a process easier said than done. It can take time, and significant staff training and capital. Even progressive developers with the best intentions are typically fraught with seeking variances to existing FSI codes implying extra work, time and money, with no guaranteed results – a major disincentive to doing anything other than business as usual.

The inclusion of Urban Standards as supplements to a city’s conventional FSI regulation could be a starting point for this change. These standards could be introduced for select areas within the city as new regulatory overlays within the larger stream of existing zoning. In progressive cities, an entirely new formal geography of neighborhoods, districts and corridors could replace land use designations as the principle regulatory armature, with a brand new set of urban standards and guidelines. A Building Types menu with detailed representations explaining the physical characteristics of each type can be included to clarify their merits and advantages to mainstream developers, who may not otherwise know of these alternatives.

Subdivision Standards can in turn help guide the design of large empty sites that are typically developed as introverted enclaves with repetitive building multiplied across the site. For instance, parcels larger than 0.8 hectares (2 acres, or the size of a 100 x 100 meter block), can be required to be broken into smaller development parcels through the introduction of blocks, streets and alleys. Based on the street type they front, appropriate lots can be designed to receive appropriate building types, which combined with the urban standards can generate a conscious neighborhood form and character.

Form-Based regulations can instigate contextual appropriateness at a lot, block, neighborhood and eventually a city scale, enabling the making of a comprehensive urban form and a rich public realm, project by project. It can provide an alternative for create multiple dwelling choices, expanding the market, enriching the community, and reviving of an entire spectrum of building types that have remained marginalized over past few decades. Recasting conventional FSI codes is a pressing task at hand, to not only control the least common denominator of uncritical densification, but to ensure than our cities do have a viable public realm to seamlessly compliment the private lives of its inhabitants.