In September 2010, the Yamuna River touched the base of Taj Mahal’s 300 m long river-facing terrace for the first time in more than two decades. Heavy rains in north India had raised the river’s water level creating a momentous event in the recent history of the celebrated monument that had fronted a near dry riverbed for too long. I am disappointed that I could not see it in person, but it delighted me that the event generated much public optimism, and more importantly, hope for the Taj’s long term future. Several studies have now concluded that the strength of the wooden shafts holding together its foundation depends on being constantly moistened by the river’s water.

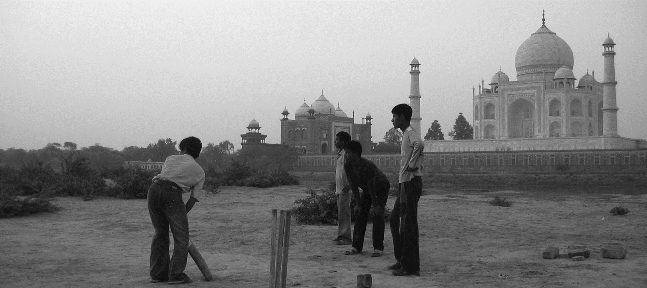

What this event also did is forced people to re-read Taj Mahal, revisit its idea as a riverfront monument, and re-contemplate the river’s significance to its experience as a place larger than the white marble-clad building. Many tourists are hardly aware of the river’s presence. Most entering through the magnificent red sandstone darwaza are simply euphoric to finally see the Taj’s dominant media image face to face – a frontal white building with four minars and a char bagh garden. Many climb up the Taj’s base, some chance behind the building and discover the river for the first time, but few know of its significance in the monument’s original design.

The Taj Mahal was conceived as a riverfront monument, as the visual pinnacle of seventeenth century Agra’s 5-kilometer long riverfront promenade. Shah Jahan would boat down the Yamuna from the landing below his royal quarters in what is now called the Agra Fort, park at the Taj’s base, climb to the top of the red sandstone terrace and thence approach the white marble edifice. This was the regal entrance and the public face of the Taj Mahal. Boating or strolling southward down the river, the magnificent promenade would instantly announce the city’s wealth and glory: To the east the mausoleums of nobles such as Itmad-ud-daullah and Afzal Khan; to the west the splendid havelis of the generals, with the red sandstone ramparts of the Emperor’s fortified palace straight in the distance. Winding eastward, was the sculptural formalism of the Taj – first seen obliquely, then frontally from beneath Mehtab Bagh, the “viewing garden” created by the Emperor directly across the river from it.

With the Mughal capital’s shift from Agra to Shahajahanabad (Old Delhi) in 1648, the riverfront released from royal patronage was gradually occupied by commoners. Several villas were sold by their owners and converted into funerary sites, with the entire riverfront gradually garnered a funerary character. By the early 19th century, during the British stronghold, it had begun to show significant deterioration as seen from much of the paintings and sketches of that period. By the early 20th century, the waters of the Yamuna had been both significantly reduced due to irrigation dams, and polluted by industrial and sewage waste. The riverfront was now used as a latrine and garbage dump, many of the mansions had been reduced to ruins, with silt covering the ghats that once connected the Taj’s plinth to the water. Within three centuries, few read the Taj Mahal’s larger urban presence; fewer still recognized that its very face had become its backyard.

But this is only one half of the Taj story. The other half remains shrouded within the walled world of Taj Gunj – the informal habitat directly south of it. This is, in fact, the former caravanserai of the Taj Mahal’s 22-hectare campus centered on the white mausoleum. It used to be a two story commercial complex also planned on the Char Bagh theme, with four enclosed quads, and two principal intersecting streets forming the heart of a bazaar with rooms and arcades. In the mid-seventeenth century, it teemed with local and foreign trades, and with merchants building their houses just outside this imperial campus, the area surrounding the Taj had become an identifiable district, known as Mumtazabad, the city of the queen. With the bazaars contributing financially to the maintenance of the campus, the Taj Mahal had, from the beginning, unified the mausoleum’s spiritual and the market’s commercial aspects into a symbiotic ensemble.

Consequent to the capital’s shift, the market too declined, and the caravanserai was incrementally possessed by local merchants and physically altered to meet their growing demands. By the early 20th century, nothing save the four gated walls once framing the central market square remained identifiable. The four quads had been filled in with haphazard development and the arcades had been added on to, reducing the streets to tenuous lanes.

Today, there is nothing to visually unify the caravanserai’s outermost gateways, and little to reveal its original form as one steps out of the mausoleum garden into the jilaukhana, the transitional court that once separated the mausoleum enclosure from the market. And it certainly doesn’t help that the Taj’s ticket booth and secured entry are now conveniently located at the jilaukhana’s eastern approach. This manipulated route requires a tourist to turn northward from the jilaukhana directly entering the mausoleum precinct bypassing the door leading to the Gunj. For most, the experience of the Taj Mahal today begins and ends with a white building and its immediate garden. Meanwhile amidst ongoing riverfront restoration efforts, preservationists also remain bent on vacating this illegal, haphazard settlement, even as its residents argue that the Taj is their rightful legacy, claiming their ancestors as its builders and subjects of the Emperor.

What an irony! How conveniently we condemn the history of a place. How easily we weed out the so called “dirty” world that surrounds the Taj Mahal even as we flaunt the white centerpiece, though it may tell but half the story. I fail to understand why origins are the only ways through which we choose to see and show monuments and their monumentality. Why can’t other dimensions – like appropriation, possession, transformation – be accepted as intrinsic parts of a monument’s evolving history, or even its irrevocable destiny? Why can’t Taj Mahal be released from its exclusively nostalgic profile, and re-read for its broader dimensions as a place that is Mughal, colonial and contemporary at the same time; as an evolving monument that is actively engaged with the city and its people thereby expanding its social significance as a phenomenon bigger and more purposeful than a single magnificent white building?

If the restored riverfront can become a new socio-economic engine for the Taj’s experience, why shouldn’t a strategic nurturing of the Gunj – its skilled labor force, stone-inlay crafts and micro-commerce – play an essential role in the Taj’s recurrent upkeep, reviving its historic relationship with the monument? What if the ticket booth was relocated at the southern end of the Gunj, so that one could walk through its informal spine, take in the re-possessed carevanserai, its ad hoc streets and houses, its shops and their crafts? What if a tourist was thus enabled to re-read the Taj Mahal for what it truly is today – a paradisiacal realm between two disparate worlds – the ruins of the drying riverfront, and the quotidian realities of the Gunj – both of whom want a stake in it?

For all its universal reverence as the ultimate monument to love, the media rhetoric surrounding the Taj Mahal is pitifully one-dimensional – limited largely to the de-contextualized presentation of a magnificent white mausoleum devoid of any larger physical and intellectual backdrop. It undermines the Taj Mahal’s deeper values as an evolving cultural icon and place. It cautions us against linear understandings of monumentality, conservation and heritage. It reminds us that historic monuments are eventually complex two-faced Janus-like constructs – one face looking to the past, the other engaged with the present, each inseparable from the other. What the Taj Mahal therefore needs today, I would argue, is not so much a glorification of what it was but a deeper reflection on what it is, and an expansion of the simplistic dialogues on its future into complex and inclusive territories.